Thousands of canisters of highly radioactive waste from the world's most nuclear-energized nation lie silent and deadly beneath this jutting tip of Normandy. Above ground, cows graze and Atlantic waves crash into heather-covered hills.

The spent fuel, vitrified into blocks of black glass that will remain dangerous for thousands of years, is in "interim storage." Like nearly all the world's nuclear waste, it is still waiting for the long-term disposal solution that has eluded scientists and governments in the six decades since the atomic era began.

Industry officials hope renewed worldwide interest in nuclear energy will break a long, awkward silence surrounding nuclear waste. They want to revive momentum for scientific and political breakthroughs on waste that stalled after the accidents at Three Mile Island in 1979 and Chernobyl in 1986, which raised worldwide fears about radioactivity's risks to human and planetary health.

So far, though, recent talk of a nuclear renaissance has focused on the "front end," or reactor construction. Engineers are designing the next generation of reactors to be safer than today's – and they're being billed as a solution to global warming. Nuclear reactors do not emit carbon dioxide, blamed for heating the planet.

The spent fuel, vitrified into blocks of black glass that will remain dangerous for thousands of years, is in "interim storage." Like nearly all the world's nuclear waste, it is still waiting for the long-term disposal solution that has eluded scientists and governments in the six decades since the atomic era began.

Industry officials hope renewed worldwide interest in nuclear energy will break a long, awkward silence surrounding nuclear waste. They want to revive momentum for scientific and political breakthroughs on waste that stalled after the accidents at Three Mile Island in 1979 and Chernobyl in 1986, which raised worldwide fears about radioactivity's risks to human and planetary health.

So far, though, recent talk of a nuclear renaissance has focused on the "front end," or reactor construction. Engineers are designing the next generation of reactors to be safer than today's – and they're being billed as a solution to global warming. Nuclear reactors do not emit carbon dioxide, blamed for heating the planet.

Waste, however, "is the main problem with this so-called nuclear rebirth," said Mycle Schneider, an independent expert who co-authored a recent study for the European Parliament casting doubt on a global nuclear resurgence.

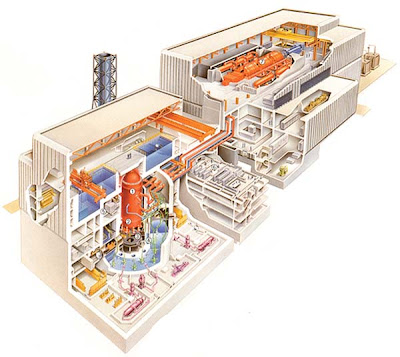

Workers at this waste treatment and storage site on France's Cherbourg peninsula, run by industry giant Areva, don't see a problem.

Though much of the technology here dates from the 1970s and 1980s, they point to a strong safety record and the 26,000 environmental tests conducted every year as evidence that the public has nothing to fear from their activity.

The tests routinely find crabs, cows and humans living nearby to be healthy. One longtime plant employee gestured toward her pregnant abdomen as proof that there's nothing to worry about. Plant officials say strict security measures rule out terrorism risks.

Greenpeace questions state-run Areva's safety figures, and accuses the government of playing down accidents and soil and water contamination.

The splitting of uranium atoms in a reactor creates the exceptional heat that drives turbines to provide electricity. The process also creates radioactive isotopes such as cesium-137 and strontium-90, which take about 30 years to lose half their radioactivity. Higher-level leftovers includes plutonium-239, with a half-life of 24,000 years.

Direct exposure to such highly radioactive material, even for a short period, can be fatal. Indirect exposure, through seepage into groundwater, can lead to life-threatening illness for those living nearby and environmental damage.

For now, the best scientific solution for getting rid of the most lethal waste is to shove it deep underground.

Another option is recycling. Countries such as France, Russia and Japan reprocess much nuclear waste into new fuel.

That dramatically reduces the volume: Forty years' worth of France's highly radioactive waste is stored under just three floor surfaces, each about the size of a basketball court, at Beaumont-Hague. Recycling, though, produces plutonium that could be used in nuclear weapons, so the United States bans it, fearing proliferation.

Not all waste can be reprocessed. The deadliest bits, such as fuel-rod casings, other reactor parts and concentrated fuel residue containing plutonium and highly enriched uranium, must be sealed and stored away.

That's what lurks 10 feet underground at this Normandy plant: More than 7,000 cylindrical steel canisters, each about the height of a parking meter, stacked and sealed upright in holes beneath the slick floor. Some contain compacted radioactive metal, the others hold spent fuel that has been vitrified into glass.

Current research in industry-leader France, which relies on nuclear energy for more than 70 percent of its electricity, is focusing on new chemical processes that would shrink nuclear waste and cool it faster. It will be at least 2040, though, before these might be put to use, scientists estimate.

Nuclear scientists' dream is a wasteless reactor, and some sketches for the next crop of reactors, the Generation IV, include those that recycle 100 percent of their refuse.

Workers at this waste treatment and storage site on France's Cherbourg peninsula, run by industry giant Areva, don't see a problem.

Though much of the technology here dates from the 1970s and 1980s, they point to a strong safety record and the 26,000 environmental tests conducted every year as evidence that the public has nothing to fear from their activity.

The tests routinely find crabs, cows and humans living nearby to be healthy. One longtime plant employee gestured toward her pregnant abdomen as proof that there's nothing to worry about. Plant officials say strict security measures rule out terrorism risks.

Greenpeace questions state-run Areva's safety figures, and accuses the government of playing down accidents and soil and water contamination.

The splitting of uranium atoms in a reactor creates the exceptional heat that drives turbines to provide electricity. The process also creates radioactive isotopes such as cesium-137 and strontium-90, which take about 30 years to lose half their radioactivity. Higher-level leftovers includes plutonium-239, with a half-life of 24,000 years.

Direct exposure to such highly radioactive material, even for a short period, can be fatal. Indirect exposure, through seepage into groundwater, can lead to life-threatening illness for those living nearby and environmental damage.

For now, the best scientific solution for getting rid of the most lethal waste is to shove it deep underground.

Another option is recycling. Countries such as France, Russia and Japan reprocess much nuclear waste into new fuel.

That dramatically reduces the volume: Forty years' worth of France's highly radioactive waste is stored under just three floor surfaces, each about the size of a basketball court, at Beaumont-Hague. Recycling, though, produces plutonium that could be used in nuclear weapons, so the United States bans it, fearing proliferation.

Not all waste can be reprocessed. The deadliest bits, such as fuel-rod casings, other reactor parts and concentrated fuel residue containing plutonium and highly enriched uranium, must be sealed and stored away.

That's what lurks 10 feet underground at this Normandy plant: More than 7,000 cylindrical steel canisters, each about the height of a parking meter, stacked and sealed upright in holes beneath the slick floor. Some contain compacted radioactive metal, the others hold spent fuel that has been vitrified into glass.

Current research in industry-leader France, which relies on nuclear energy for more than 70 percent of its electricity, is focusing on new chemical processes that would shrink nuclear waste and cool it faster. It will be at least 2040, though, before these might be put to use, scientists estimate.

Nuclear scientists' dream is a wasteless reactor, and some sketches for the next crop of reactors, the Generation IV, include those that recycle 100 percent of their refuse.

Source: Associated Press|By ANGELA CHARLTON

Blogalaxia:nuclear fotolog Technorati:nuclear Bitacoras:nuclearagregaX:nuclear

No comments:

Post a Comment