A rising middle class in Asia is developing a taste for meat, so crops that might go to feed people are being diverted to cows and chickens. Within the next year, China will become a net wheat importer, driving food prices up just as it's driven up other commodity prices this decade.

For the poor, this booming commodities market means more famines the United Nations and the World Bank simply can't afford to alleviate.

Yet investors might find some opportunity amidst the misery. Two years ago, Deutsche Bank tarted work on a global agribusiness strategy that debuted in September 2006. It's managed by 37-year-old Ralf Oberbannsheidt, who has $2.6 billion in portfolios available to investors in Japan and Europe. He's up 48% so far, buying stocks like Monsanto, Archer Daniels Midland and Bunge Limited. He also invests in fertilizer companies and some shipping concerns. The boom in this sector is akin to the boom in oil, but more sustainable.

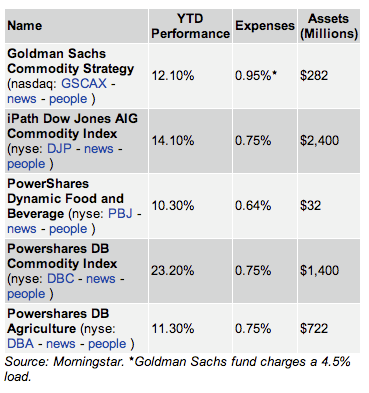

Food Funds

As a slowing U.S. economy threatens to bring down oil prices, but wheat and corn prices probably won't drop because of scarce supply. In fact, the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization warns that wheat production is falling and could be off 10% to 142.6 million metric tons in 2008. And in the U.S., an increasing amount of corn is being diverted from the food chain to be processed into ethanol, for reasons frankly more political than environmental.

The implications for the world are grim. If the U.N. is right, the global population will reach 9 billion people by 2050. Meanwhile, the Earth is running out of farmland because of population growth and sprawling cities. Fifty years ago, there was an acre of arable farmland per person--there's half that now. That's why Oberbannsheidt is interested in aquaculture. Before he became a securities analyst and portfolio manager, Oberbannsheidt worked for a freshwater shrimp farm in Northern California, and he remains fascinated by how well the critters can be manipulated for flavor and durable shipping.

"You take away land so that people can live in the city," Oberbannsheidt says. "When you live in the city, you have a greater life expectancy and your income is probably higher."

When incomes reach between $3,000 and $5,000, as they're approaching in India and China, people tend to give up rice and cereal in favor of meat, poultry and fish, generally in that order. Protein intake rises 15 grams a day. "If people would only eat wheat and corn the [potential food shortage] problem would be solved," he says. "But I'm not a vegetarian, don't get me wrong." Half of the wheat and corn crops produced every year go to cattle. He does see opportunity in fish, though, since it's generally a cheaper source of protein than beast and fowl.

Two years ago, when Oberbannsheidt started looking seriously at agribusiness, nobody on Wall Street had even factored biofuels into the equation. Now governments have to make a choice between feeding people and fighting global warming. "The first job of government is to feed its people," Oberbannsheidt says, but in the European Union, where mass starvation isn't a looming problem, politicians can--and are--meddling.

The E.U. is hurting from high wheat prices, which are threatening to cause inflation on the continent. But the E.U.'s own subsidies for biofuel are contributing to the rising prices. The E.U. could have both enough food and enough biofuel if it allowed genetically modified crops to be used for biofuels. Or even better, says Oberbannsheidt, the E.U. could lower trade barriers against importing biofuels from Brazil, which is about the only place on Earth where biofuels make economic sense, anyway. But neither option seems politically viable in the near term, so Oberbannsheidt expects European commodity food prices to remain high.

One thing the world obviously needs is greater productivity from its existing farmland. Oberbannsheidt believes it's possible through fertilizers, particularly potash and phosphate--but don't expect miracles. He recently went to Montegrosso, Brazil, because he thought that companies with Brazilian land holdings would be worth buying. Brazil is a kind of El Dorado for agricultural commodities investors, because its climate allows for three growing seasons rather than just two. Farmers there can quickly capitalize on global demand by switching from wheat to corn to soybeans more quickly than farmers in the rest of the world.

Oberbannsheidt returned disappointed. The soil quality wasn't that good, he said. Even if it had been, there's only one rail line that can be used for shipping to ports. There's no point in increasing yields if the product can't get to market. He found the same problem in Vietnam, where rice yields have been increasing 10-15% a year, but the infrastructure for shipping it can't keep up.

Oberbannsheidt returned disappointed. The soil quality wasn't that good, he said. Even if it had been, there's only one rail line that can be used for shipping to ports. There's no point in increasing yields if the product can't get to market. He found the same problem in Vietnam, where rice yields have been increasing 10-15% a year, but the infrastructure for shipping it can't keep up.

Everything would be fine, he says, if the world's governments would "solve the infrastructure bottleneck, invest in research, allow for GM in biofuels, and build better water and irrigation systems." That's exactly what Oberbannsheidt doesn't see happening. Instead, he sees a "biofuels versus feeding the world" scenario. That's a frightening prospect for the world's poor, and potentially, for everyone. But it should keep Oberbannsheidt's portfolio humming along.

Via: Forbes|by Michael Maiello

Tags: